An Interview with Sri KVN

Courtesy of Sruti Magazine, Issue 27/28, December 1986. SRUTI Editorial Associate M.S. KUMAR interviewed Palghat K.V. Narayanaswamy when the vidwan was selected to preside over the 60th annual conference of the Music Academy of Madras.

The Learning Experience:

Can you tell us about your training under Mani Iyer ?

A few mridangam disciples of Mani Iyer, including Palghat Raghu, would gather at his house every evening. I would also be there. Mani Iyer would have a kanjeera in his hand. He would ask me to sing. I would sing, maybe a varnam, as Mani Iyer guided the disciples on how to play mridangam for that varnam. At the same time, he would explain to me how that varnam should be sung in two kalapramana-s [tempos].

Mani Iyer would ask me to sing the same song many times. The beauty of this was, when you practiced the kriti over and over again, you got new ideas every time you sang; you developed fresh sangati-s, enhanced the rendition with each attempt. But it is while you do this that the guru plays a key role in your developing into a musician. You shouldn't end up singing anything you feel like; the guru should correct you when you sing a wrong sangati or a phrase that the raga doesn't permit. Our music needs a guru basically for this, to tell the disciple what should not be done. In his formative years, it is sufficient if a student leams merely what should not be done. What should be done can come later, can be learnt slowly. But primarily the don'ts should be known.

But many singers who sing wrongly, say, when asked about it, that that was how they were taught. What do you say to that ?

That only shows their lack of grasp. It's convenient to blame the teacher for your own shortcomings and your inability to master what has been taught. The student should not merely copy what his guru says or sings. He must be able to divine or at least conjecture what the guru has in his mind when he sings in a particular way. Actually, this is what gurukulavasam is all about. Gurukulavasam is a system of slowly and steadily gaining a true understanding of the guru's musical ideas and his approach to music. It is a framework provided to the sishya to educate himself on these things by being close to the guru and observing him keenly and sensitively all the time.

Modern educators believe that the student is all-important and that the onus is upon the teacher, the guru, to appreciate the student's needs, strengths and weaknesses and to adapt the teaching to suit the student's need. Does gurukulavasam fit in with this conception ?

The guru has a major responsibility: he should assess the capacity, the potential of the sishya and steadily educate him to reach and realize that potential. If he is going to thrust all his knowledge willy-nilly on the disciple without any regard for the disciple's grasping powers, all will be lost. The guru should teach in a manner that benefits the student later to become a thorough musician. The sishya also has a tremendous responsibility, as I said earlier, of understanding what the guru is doing. In the initial stages, he may not be able to do this, but the yearning should be there, the unabated thirst for learning and mastering every little thing the guru says or sings or does. If this thirst is present, the disciple will surely have God's grace.

What was Mani Iyer's reaction to the family's request to send you to Ramanuja Iyengar for training ?

When we asked him about it, he said: You should go to Ariyakudi only when you have become proficient enough to perform. There's no point in going to him before that calling yourself a disciple of Ariyakudi and saying that were under his tutelage for sometime. So he sent me for additional prior training, first to C.S. Krishna Iyer and then to violinist Papa Venkataramiah. Papa protested and said : I am not a vocalist. What can he learn from me ? Mani Iyer told him: Let him just listen to you, absorb your playing, your style Please take him to all your concerts and make him listen. extensively. If you feel like, you could teach him some songs, a varnam perhaps. That's entirely up to you. But he must be with you.

Tell us about your learning experience with Venkataramiah.

Papa Iyer was an extraordinary musician. He would get up at four in the morning and practice a varnam, say, in Kalyani raga or song he took up, he would practice in such pitiful detail that he would leave nothing undone, no nuance unexplored. I was with him, listening and learning. During Second World War, many left Madras. He went to Tanjavur and I accompanied him. Occasionally, he used to teach explicitly but far more important was what I got from him listening to him play. I think 'kelvi gnanam' [knowledge acquired by listening] is for our classical music very crucial. It was for this that people used to sit in nagaswaram kutcheries well into the small hours of the morning in the old days. Listening to good music helps to acquire a refined ear. For this reason, one should not listen to low grade music but only to good music.

Now, tell us about your training under Ramanuja Iyengar.

I entered Ariyakudi's household for gurukulavasam when was 19. Earlier, when I was about 11 years old, a great soul called 'Gandhi' Krishnamurthi, of Kalpathi, was like a mentor to me. He gave me a lot of encouragement. But he was disciplinarian and he wouldn't allow me to sleep in the afternoon or develop any such reprehensible habits. With this the background, I went to Iyengarval with a resolution and clear mind: to forget myself and entirely submit myself to serve him, to take care of all his needs and do my gurukulavasam sincerely, no matter how difficult it was, so that I could learn all I could from the great man. This is really the essence of gurukulavasam. I would describe those years under Iyengarval as the key to my developing into a full-fledged musician. I used to go to all the concerts of my guru. A sishya has be very observant when his master performs. He should note minutely a number of things: how the guru selects the song for the recital, why he sings a particular song he sang only the day before, why it sounds so fresh and so different from the day before, how the voice is modulated and so on. He must note how the guru ends the concert as well as the different items. He must reflect on the format of the recital and a himself why his guru limits the duration of a particular piece or the recital itself when everyone feels he should sing more and more.

Can the sishya clarify his doubts on these matters with the guru directly ?

Oh no! He shouldn't ask. He should analyze himself and infer the answers. Mani Iyer, when accompanying Iyengarval, used to indicate to me by sign language -- by a shake of the head or the raising of the eyebrows -- when he wanted me to observe and file away a musical nuance or finesse that my master was rendering. He would explain to me later, after the concert ended, the importance of these things my guru did. This is one of the great advantages of gurukulavasam in my opinion.

Ariyakudi himself wouldn't ask you, would he, whether you noticed how he did this or that ?

My god, no. That he wouldn't and I don't think he should have. It's up to the disciple to be sensitive to these things and enrich his musical knowledge.

The most outstanding quality of my Anna's (Ariyakudi's) music was its felicity, its fluent ease. The music would sound so simple that I would think I could sing it straight off. But when I attempted it, the results would be disastrous. I wouldn't get the finish, the sangati-s simply wouldn't fall into place the way they did when he sang. It used to be a bugbear with me and I used to agonize. But the yearning grew within me--you could call it an obsession even--that I must sing like him.

It got to a stage that I became totally frustrated and asked myself: when am I going to achieve anywhere near the musicianship of Anna ? The whole exercise appeared a futile one, an exercise in mere wishful-thinking. Abruptly one day in December in 1946 or 47, I decided to forget music altogether. I ran away.

[Narayanaswamy recalls at this juncture the brief episode of his leaving his guru and trying to enter Gandhiji's Wardha ashram, and of his eventual return, after a couple of months, to Ramanuja Iyengar.]

When I returned to my guru, like a truant child, I realized how much affection he had for me. He did not openly show his affection to any of his disciples--in fact, no guru should--and some observers felt and said that 'Iyengarval treated his students badly' but this was not at all true. He could never hurt anyone, he was like a child himself. He didn't get angry at me or anything like that. He simply asked me: What is this ? Here I was wanting to make a musician of you and you just run away without a by-your-leave ? Why did you do it ? I apologized profusely to him and told him I had been a fool to go off like that. But he was happy that I had come back. He asked me to sing with him in a recital he was giving that day. But even before he said anything, I had already taken over all the other tasks to be done for him that day -- washing the clothes. cleaning the vessels for water, tuning the tambura to perfection, etc.

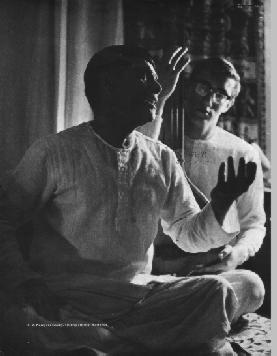

With guru, Chowdiah and Mani Iyer

One of my main jobs with him always was keeping the tambura tuned flawlessly. He attached very great importance to it. That in fact was a significant aspect of my gurukulavasam, anticipating the sruti at which Anna would sing and tuning the tambura accurately to that sruti.

Did you have explicit learning sessions with your guru ?

He used to give such sessions occasionally in Kumbakonam. in the house of Dhanammal. Iyengarval's wedded wife was in Karaikudi: this Dhanammal, in Kumbakonam I should say was his 'pathni'. She was a nice person and she herself used to sing. Anna would sometimes sit down to teach her, in the evenings, and I used to look forward to these sessions enthusiastically. She was slow to learn and Anna would repeat the sangati-s four or five times for her to get them right. That was immensely beneficial to us, naturally.... Chokkiah Chettiar of Devakottai--he died last year--who helped persuade Iyengarval to accept me as a disciple, used to tell me: Even if you get the sangati correctly the first time, don 't sing it correctly. Because, if you do that, Iyengarval will go on to the next sangati and will not give you the benefit of hearing it again from him. Sing it wrongly, make small mistakes deliberately ....

From what you say, it seems only a student with extra grasp, with more than average sensitivity and imagination. can learn and benefit from gurukulavasam. Isn't that correct ?

Much depends upon the IQ of the student, yes. I mean, not only the intelligence but the interest quotient too. It's up to the sishya to glean the knowledge from the guru. It can't be expected that the guru should bring out everything he knows and place it before the student clearly and easily for him to lap it up. A lot of work has to be done by the disciple. I'll give examples from my training under Anna. He would say. for instance: Don't sing to yourself: Sing out, throw up your voice for all to hear. What meaning I made of this advice was entirely up to me. I had to interpret it using the context in which he said it. To get the full import of such advice, I had continuously to observe how he gave out his voice, how he sang. But, in a fine art like music. one cannot literally translate the guru's advice. Like, in this instance, singing out vociferously didn't mean I had to shout. And there would be times when I shouldn't be singing out loudly. Timing, a sense of propriety, is very, very crucial to the success of a musician, of his performance. My master had an unbelievable acumen for this, a marvelous feel for what would get across to the audience. He would size up the audience in the first few minutes of a recital and decide with uncanny precision the raga-s, the kriti-s and the general approach of that day's kutcheri. The listeners would obviously go back delighted. Some would boast: Iyengarval sang such-and-such a song which we wanted him to sing today, you know. A musician must develop a very close empathy with the listeners and should understand the rasikas' psychology perfectly. Otherwise he cannot satisfy the rasikas.

I went to Iyengarval in 1942 and until his death was with him off and on. The three of us-Rajam Iyer, Madurai Krishnan and me--shared his time. One of us would be with him always. I got married in 1948 after that I didn't stay with my guru. even though I continued to go to his house almost daily and serve him. It was I who almost invariably accompanied him on his travels to the North. In 1965 I went to a Wesleyan University in the U.S. and I didn't see him after that, for he died in 1967. It will always be a sad thing for me that I couldn't be with my guru in his last days.

Before we go off the subject. I must mention another outstanding phase of my learning experience. This was when I came under the tutelage and influence of Bala [dancer Balasaraswati], Viswa and their mother Jayammal This was around 1964 or 1965. I was greatly benefitted by this association. Theirs is very high class music, chaste, grand and you might say truly classical. Viswa particularly became a great friend of mine.

You mentioned earlier that. by observing your guru during I practice sessions and recitals, you learnt and mastered the various aspects of classical music. Did you learn these in any other way also ? or from someone else ? Could you talk some more on the learning of these techniques ?

KVN in the 1950s

I notice that we, the modern-day artists and other people have a feeling that we are far more intelligent than the people of yesteryears. The attitude is: What have they done that we cannot do better ? I think it's a terrible attitude to take, especially in Carnatic music. What we should think of now is how has the treasure of music come down to us ? Generation after generation of musicians have sung, created and perfected this great art and they have got it to a stage where it is beautiful. A great deal of dedicated creativity and imagination has gone into the process. We should marvel at this evolution and transformation, instead of looking at the finely chiselled, exquisite, yet simple finished product and saying: Surely, I am capable of much more than this. We should be eternally grateful to our predecessors for their contribution.

In science and technology, you can look ahead: what more can be done, what new discoveries and inventions can I achieved ? In music, it is necessary to look back. To study, depth and in extensive detail, what the previous generation and the generation before that did and so on. To learn lesson from their experiences, their creative exercises. their experiments. Merely hankering after something 'new' but forgetting the old is, in Carnatic music at least, not advisable at all. What can be new ? Are we going to sing off-key ? or off beat ? Can we, in other words, relinquish sruti and laya ? The great masters before us have given us sruti, laya, sahitya and sangati-s. In anything they did and in everything they passed on to us, there is beauty and there is moderation. They carefully eschewed dramatization. studiously avoided excesses in presenting either the music or the bhava. If we would change all this and give our recitals an overdose of emotional or musical colour. merely for the sake of applause, then we would be degrading a stately art for momentary gains -- that's all.

How did you circumvent this trap yourself ? How did your training help you discern and avoid this kind of excess ?

Ariyakudi did everything in moderation, in the correct quantum. He didn't move a millimetre away from sampradaya. He didn't sing anything outlandish. It was simply not in him. He would in fact tell us: You know, you should have heard Tirukodikaval Krishna Iyer play this sangati. Or Saraba Sastri or Veena Dhanammal. He would quote extensively from the repertoires of these musical giants and make us alive to the musical heights that were reached in the earlier eras. The cumulative effect of his listening to so much of refined music was reflected in his own style of music.

So your learning was largely from listening to his recitals, occasional practice sessions with him, some guidelines he used to give, your own practice.

Mostly yes. But, I also learnt from my experiences in singing with him. Accompanying a singer is far more difficult a task than solo singing, y'know. The assembled audience wants to listen not to the accompanying singer but the main singer. The second voice should therefore be always subdued. well below that of the main singer. In fact I would say the disciple s voice must be audible only to the guru. The guru allows the disciple to sing alone for the latter-s own development only; so the disciple must be happy to have that opportunity of singing along and learning at close quarters, picking up the guru's musical ideas and creativity. He should therefore be very careful, very alert -- first. so that he doesn't hinder the guru, and second, so that he helps make the concert a success.

But, even in this secondary role, there is so much that a disciple can do. I'll give you an example. Sometimes when a disciple is sitting behind the guru, strumming the tambura and singing softly, he would realize that one of the strings is not correctly tuned or has got out of tune. The guru would also notice this. What should a disciple do in such an event ? First he must see if he can retune the wayward string correctly by adjusting the beads but without stopping the strumming. If he is not confident of doing this, he must continue strumming the correctly-tuned strings and leave the non-aligned wire out totally, so that it does not spoil the guru's sruti.

Strictly speaking, a musician shouldn't sing without tambura sruti unison but this is what one can normally do in a pinch. In exceptional circumstances like this, the sishya should have the presence of mind to save the situation by quick action.

Performing with two gurus on the side

Career, Goals and Achievements

Were there any interesting or important events during your gurukulavasam or early in your concert career ?

Yes. Some six months after I'd joined Iyengarval for gurukulavasam, he had a concert date in Tirunelveli. The violinist billed for the day--I think it was Papa--hadn't turned up. My guru said: Narayanan is there, we'll manage. He used to call me Narayanan. I didn't know what to say when he told me: We haven't got a concert class violinist with us for today's 's concert, so you should sing as an accompanist whenever I tell you to, during the concert. He guided me and I did the job as best as I could. Fine. But I should have kept quiet after that, shouldn't I ? What I did was tell everyone that I had been asked to accompany and sing raga and swara-s after a mere six months of tutelage. So Anna was besieged with queries on how he could entrust such big responsibilities to a 'paiyan', a mere boy. He got into quite a jam on that one, I can tell you. After this incident he used to tell me: It is not enough if you know music to be a performing musician; you should know propriety and decorum as well.

Let me relate to you another incident which I think the Hindu critic reported. Iyengarval was scheduled to sing at the Music Academy accompanied by Papa Venkataramiah and Mani Iver. He telegraphed from Kumbakonam to say he wasn't well and wouldn't be able to make it. V. Raghavan [one of the Secretaries of the Academy] immediately announced, even without checking with me, that Ariyakudi's disciple K.V. Narayanaswamy would sing the next day with the same accompaniments. When I listened to the announcement, my blood ran cold. Two great musicians who were my gurus to accompany me ! Somehow I managed the concert the next day. I bowed to my gurus before starting the concert and both gave me encouragement and good cheer.

Tell us about your other performances and your kutcheri days then and now.

I started giving recitals when I was 10 probably, in the Kollangode temple. But my first real concert was in the Tanjavur Pillayar temple with Tiruvalangadu Sundaresa Iyer and Mani Iyer as sidemen. It was organized by Mani Iyer himself.

How many concerts do you sing on an average every month or every year ? Some musicians seem to think that they should sing in public as much as possible in their prime of life and make as much money as they can when they are in demand. The reason is said to be that they don't have any provident fund or old-age insurance and that they should provide for their old-age by performing as frequently as possible. even if the quality of music suffers as a result. Do you have any comment on this situation ?

There's a lot in what you say. The musician can perform in concerts and be in demand only for a certain period of time. He would naturally like to earn as much as he can in this period. But one thing that can be done is to give musicians more amenities and tax benefits than they get nowadays so that they would feel a lot more secure.

Didn't you have a similar urge when you got into the limelight and everyone wanted to have your concert ? If you did, how did you overcome that temptation to overstretch yourself and your voice ?

The answer I think lies in the way I was brought up in music. The emphasis was not on becoming a pro and making money by giving performances. I wasn't ever told: You should become a musician of outstanding repute and should achieve a great name in Carnatic music. No such goals were set for me when I started learning. That, I feel, is the key. I somehow imbibed the thought, in my childhood, that worldly approbation was hardly the thing to aim for, that a Carnatic musician's aim must be of a different kind and much higher. I believe that a musician--or any other person--should set his goal so high that he isn't tempted at any time to think that he has exceeded his goal. If a musician starts thinking that he knows everything there's to know and that no one else can touch him, then that can be his end. Vinaya--modesty--is the most valuable trait a musicians can have. He should truly believe that what the other person knows could be more than what he does. He should be genuinely awed by the great treasure our ancestors have left for us and not try to belittle it. The preoccupation of a musician should not be with how well he sings or what a great singer he is. Rather it should be with what more he has to do, what else he can learn and sing.

KVN in the 1960s

The trouble is that music doesn't have the kind of following it used to have earlier. In such a situation wouldn't the musician be justified in making the most of his available opportunities so that he can make a livelihood ?

Wel1, can't he reduce his wants ? Many of today's 'wants' are not necessities, really. So a musician can cut down or these demands of his own -- for a television set or a VCR -- and lead a spartan life. But he shouldn't perform as he likes and compromise on quality.

In fact, when a musician becomes very popular and is much sought-after, there is a whole set of youngsters who would regard him as their role model. In such a situation I think his responsibilities increase manifold. He has to be much more careful about what he sings and how he sings. He has the onus upon him to create and sustain a high quality of listening as well as performing. If he drops his quality and pays more attention to cheap ways of popularizing his music, the people who regard him highly and believe he can't do anything wrong would imitate him. In this way he would be doing incalculable harm to the chasteness of our music. A musician in the pinnacle of fame should be very watchful of his voice, his sruti-suddham, his laya control. He should be concerned about singing melodious rakti-purvaka music, selecting ennobling kriti-s of great masters. He should even get listeners to hear the sruti-unison exercise at the beginning of the concert. There is much pleasure even in the simple sunadam of the tambura beautifully aligned to the concert performer's pitch.

As a performing artist, do you think there is a change in listening and appreciation which will require you to adapt your singing style and kutcheri format ? How do you see yourself as a performing musician for the next few years at least ?

Where's the need to do all kinds of things to give Carnatic music mindless popularity ? Such emergency treatment is neither necessary nor will it do Carnatic music any good. But there is perhaps the need to encourage a clear understanding among the modern generation of the great contributions of our elders and their ancestors to the cause of classical music. The approach shouldn't be to decry what has been done in the past. but to inculcate in the young a feeling of respect and appreciation for what great things have been done.

A performing musiclan has a sacred duty to fulfill. a clear responsibihty to the art to discharge in each of his recltals. He should approach the task with devotion and respect. He must uphold quality and yet sustain interest. He should not blame the listening public and lament about the fall in music appreciation standards. That is sheer hypocrisy. I ask you, if film producers decided to give 10 chaste films portraying bhakti, do you think the public won't see them? The fault is the producers for coming up with trash which is also seen by the public. Likewise. a performing musician should follow a changeless policy and sing only good classical music. He should try to 'culture' the ears of the listening public to appreciate it. My guru used to regard the concert hall as a temple and the listeners as gods and so his music was always of a high quality. He used to say: People come from far and near with the sole purpose of listening to us. We should not disappoint them. We should give our best with utmost sincerity and without holding back. That was his motto. If this means giving my life on the dais. I'll be happy to do so, he would add. When a musician makes such a sincere attempt to give high class unadulterated classical music. he'll have listeners aplenty I can assure you. As I said earlier. it may be slow: some ten persons who listen to such music and are enthralled will tell ten more and these would attract ten more--and so on it would go. A large band of first-rate listeners will emerge over a period of time. I believe that what is good is indestructible. God ensures this by an unrelenting supply of great sages who keep the good things in life going strong.

KVN in concert in the 1960s

Can you tell us about your achievements?

I'm not able to understand some people saying, "I've done this. I this done that." How can anyone talk like that? Can I say that I know everything there is to know about music ? Wouldn't that be sheer nonsense ?

An artist must die dissatisfied with what he has done. No musician can say with a clear conscience that he has reached the end. The hunger for learning something more, doing something more. and better must remain unappeased throughout his life. The degree of this unfulfilment may vary, but to a real artist there can never be total contentment.

So what should one do? In our youth we have so many thoughts, so many ideas -- some good, some wasteful. As we grow older, we slowly shed the wasteful. the unnecessary. the ridiculous. We become mature through life's experiences, become discerning and acquire the ability to sift and retain only the good. In art, in music, it is the same. When we are young, the body is strong and we entertain all kinds of ideas. We reel off swara-s and briga-s in showers, we scintillate audiences with power, we compel audiences to applaud. We make a name for ourselves as performers capable of great things in music. We need time, we need experience, to come to terms with our art. But, at some stage, shouldn't we cultivate 'sowkhyam' in our music? And restraint? Shouldn't we, for example. sing a raga briefly and still capture its true identity? I used to hear Veena Dhanammal play Sankarabharanam in my youth. She would reveal the raga swarupa in all its glory in just a few minutes. We should also aim for that instead of wasting time searching for Sankarabharanam all over the place in a long alapana. Searching is necessary. of course, but it must be well directed.

An essential prerequisite for this to happen is suddham, purity, in personal life also. A musician should have satvik habits with the emphasis on moderation and understatement; he should be god-fearing and devoted to the music, and he should eschew any activity that can upset his physical well- being. As a Tamil proverb has it, how can one draw a picture without the wall [the canvas] ? We have lost so many un- paralleled musical giants because of problems in personal life. For instance, S.G. Kittappa died unnaturally young and we can never quite make up for it. Then Rajarathnam Pillai, Mali....

In summary ....

We should not change our music, our singing quality for what is loosely referred to as 'bahujana priyam' or popularity. There was applause in the old days and there is applause now, but I see a lot of difference. Applause used to come down In a shower in the olden days, signifying genuine happiness of the audience at having heard great music. Nowadays, there is that routine applause we hear all too often at the end of an item-pitter-patter. pitter-patter it goes -- whether the item is good or not. So applause can hardly be good enough grounds for changing our music. On no account--and I say this with all the emphasis at my command--is there a need to depart from tradition, to shift away from sampradaya.

What do you mean by sampradaya ?

I suppose I must explain what I mean by sampradaya: Sampradaya sangita essentially comprises sruti suddham, laya suddham, kalapramana suddham, proper alignment of the words in the sahitya to the music and distinct and correct pronunciation. Besides, to get really close to traditional Carnatic music, a musician must know the rudiments at least of five languages--Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam and Sanskrit. In all these languages there are great compositions which no artist can do without learning.

KVN, Veeraraghavan, Palghat Raghu, Mrs. KVN (tambura) and Toufiq Touzene (sruti box)

Chief Casualties of Today's Music

Purity of sruti and purity of note positions on the scale seem to be the two chief causalities in Carnatic music today, probably because of the demand for spectacular music and the lack of time and patience on the part of musicians, both young and not so young. What can be done to remedy the situation ?

Yes, sruti suddham and swarasthana suddham are two areas in which we have slipped badly in Carnatic music. Sruti is probably the most important thing to a musician. For getting sruti gnanam, there's no better method than tambura-playing. But the alignment of a tambura is a technically difficult task for a new learners. Such people can use electronic sruti boxes, which are easy to handle, or even the plain old-fashioned sruti box with bellows. Staying perfectly in sruti and practicing-that's all there is to good music.

There are many overtones in the sound of a tambura. Therefore there is need for one to be finicky about the wires to be used in the tambura. While I was teaching in college, I used to devote one whole class-period to train my students in this. I would say everyone should know how to handle a tambura and align its sruti. Just as a mridangam vidwan attends to his mridangam and keeps it correctly tuned and serviced, the vocalist should regard the tambura as his instrument and keep it perfectly aligned and neat. The tambura and sruti are what make the music possible.

I had once been to AIR-Bangalore where I met this tambura artist--I'm sorry I don't remember his name. It was a joy listen to the sound of his tambura, such was the flawless perfection with which he had both maintained it and tuned it. He said to me: "This [keeping perfect sruti] means much more to me than just a job."

On another occasion, a disciple of Pandit Jasraj strummed the tambura for me at a radio recital in Bombay. After finding what my sruti was, he got the tambura aligned in less than two minutes. It was absolutely miraculous, even divine. I confessed to him: I can't do it so superbly or so quickly. I kept watching him to try and understand the secret of mastery over the instrument. At the end of the recital, he complimented me on my singing but I told him that a lot of credit for it belonged to him and his tambura expertise. Later I wrote to AIR-Bombay commending the supreme quality of this tambura artist and telling them they were lucky to have such a gifted person on their staff.

I must also mention this boy who was among those I was teaching when I was in America. He wanted to be a tambura player only. Really! He said to me: "Teach me to handle tambura perfectly. That'll do for me." I said I would do that gladly and I taught him for a month. He perfected the art by constant practice and could derive immense pleasure merely playing the tambura and listening to its drone in perfect alignment with sruti.

One of my dreams--up to now unfulfilled, alas! -- is a each of us should have a first-grade tambura, beautifully tuned and perfectly aligned and, every day, we should go to sleep and get up in the morning listening to the tambura sruti for a few minutes!

I shouldn't lose this opportunity to say that we need to improve the lot of the artisans who make tamburas. Many of us are concerned with sruti and the tambura but not about those who make the instrument. There are government-aided institutions and fairly large commercial establishments producing tamburas and other instruments but a large number the producers are private individuals. They should be well supported with finance and materials. Good jackwood and other tree wood which can be used for making tamburas should be given to them in sufficient quantity and their craft must be sustained and encouraged in other ways as well.

As regards swarasthana suddham, there is nothing else that will help a musician to achieve it except practice. When we were in San Diego a year or two ago, we stayed with an Indian compatriot --Ananthan-- in his house. He told us about an experience he had when Bhimsen Joshi and his party were similarly staying with him earlier on. As he narrated it, Panditji was occupying a room in the basement. Every morning he did riaz from four to six. He did sadhakam only in the mandhra stayi [lower register], staying long in each swarasthana, all the time perfectly aligned to sruti. Anantha would listen to Joshi Saheb for the entire two hours as he practiced 'aakaram' and 'eekaram'. Now, how can a musician stray from sruti or the correct swara position if he is so painstaking?

Quality of Listening

Has the quality of listening changed from the olden days ? And if it has, is it for the better or worse ?

There is a difference in the quality of listening between then and now, yes. I'm not talking about the mindless applauding. This is a practice we seem to have picked up from the West. There is definitely a solid group of concertgoers who are well-informed and discerning. In general also there is an increasing demand for 'sowkhyam' [serene quality] in music and people have started turning up in larger numbers to hear music which belongs to this variety. No doubt a large part of the Carnatic music crowd of yesteryears has moved into other spheres of faster entertainment. My suggestion is, leave them. I think that the smaller group which is keen on even-tempered, classical, sampradaya sangita is slowly enlarging. That's good enough for me. It can't grow any faster. When those in the other group get tired of the faster, more titillating music, they'll seek refuge in Carnatic music. I don't mind waiting for that to happen, even though I know the wait will be a long one.

Audience Behaviour

You have some views on audience behaviour ?

The members of the audience must sit through a concert instead of walking out halfway or, worse, in the middle of an item. That must be a discipline, an unbreakable law, whoever may the listener be, whatever his other problems.

You might have seen in the Academy and in other places that when the musician on the stage keeps the tala, so do most of the listeners, loudly and forcefully slapping their laps. The sounds of their time-keeping reverberate through the hall. This is highly disturbing. On one occasion, Palghat Raghu was playing a rather complicated korvai during the tani avartanam and I was keeping the time vigorously. So were many others, slapping their thighs just as vigorously. I had to raise my left hand and implore everyone else to stop. If I had not done that, the moment of alignment of that korvai with the eduppu could have been spoilt. It was something like a cliff-hanger that Raghu was playing; and even a second's misplacement would have resulted in a mess. In such a situation, particularly, the audience should keep quiet and allow only the main singer to keep time; the mridangam player would have only one person to watch and compose his korvai-s. Listeners must develop the ability to keep time mentally, or at least softly, out of the sight and earshot of the performing team. Otherwise it will disturb the singer and the mridangam player.

Like this, there are many sensitive aspects in a music concert in which the performers and the listeners must develop mutual understanding and help to achieve the common good of both. In fact the singer shouldn't be shy of expressing these points openly to the listener. Much misunderstanding can be avoided if he would speak up.

You have done so now. Let's hope there'll be positive results soon.

Teaching: Hazards, Effectiveness

When you teach ladies or young boys, you have to sing at a very different pitch from your usual sruti. Does this not affect your singing voice ? What do you do to prevent this from affecting your voice ?

That's a good question.

The idea is to learn and perfect the method of practicing music, the method of aligning oneself to sruti and singing. In the North, there is so much attention given to sruti unison. This is something we must commend and follow.

In learning to sing, the key should be to learn the perfect use of voice. There is no need for separate breathing exercises; correct singing is the best exercise there can be. There are seven pronunciation techniques-aa, ee, oo, ae, i, ow and humkaram, as they are called--which must be assiduously practiced and perfected. In fact, this must be done from childhood. Children must be taught to stay on a given pitch using, for instance, aakaram -- singing aaaaaa --and slowly to increase the duration of the stay. This will help develop the ability to give karvai-s on a given note without pitch variation. Chembai was a great master in this art-he could stay for eight avartana-s on the same note without faltering on the sruti, you know. He would ask you to count. What's required is not so much physical strength as sadhakam [practice] and strength of the mind.

Sruti-gnanam and laya-gnanam are paramount in the learning and practice of good music. One should do sadhakam with kalapramanam, one should not learn the raga-s and sahitya-s first, then the tala. One has to learn them together at the same time; otherwise one will not get a grip over tala ever.

But let's get back to my question--if you teach in different sruti-s, what should you do to preserve your concert sruti and protect your voice for the kutcheri ?

When I teach female students, I do face this problem that at times I have to sing at a very high pitch, at others at a low pitch. This can't be avoided.

But it doesn't seem to have bothered your voice at all--you have been able to maintain voice fidelity despite this occupational hazard. How have you managed it ?

One thing that a singer shouldn't do is overdo the practice. All this stuff about getting up at four o'clock in the morning and singing in the tarastayi [higher octave] is unnecessary acrobatics. Shouting in tara stayi in the morning should be avoided totally. Early morning practice must be done in mandhara stayi only.

To answer your specific question: the teacher should develop the knack to teach girl students without straining his voice too much. He should give his voice softly and gently so that the timbre of the voice does not break. The other thing, the more important thing, is not to keep singing and yelling along with the student all the time. He must make the student sing the sangati-s many times and confine himself to correcting and guiding them. The principle is the same whether the student is a female or a male. The idea is of course to impart knowledge to someone else; but in doing this, the teacher must be able to reduce the strain on his own voice to the minimum possible. He must lower his sights somewhat and try to teach at a level which the disciple is able to understand. Say, if there's a sangati I'm teaching which the student isn't quite able to catch, I can go on singing the sangati any number of times; the student will probably keep singing it the way he has been able to interpret it. Repetition on my part would be a waste of time. Intelligent guidance is what's required in such a situation. So, I must try and spell out the sangati in a lower tempo, get the student to follow the variation at that tempo, and then ask him to speed it up. If you don't vary your speed but expect him to learn the sangati at the faster pace, he will probably never get around his difficulty.

But doesn't all this put a lot more strain on you while teaching ?

Yes, but only mental strain, strain upon the intellect. Not on the voice. And I don't make the mistake of physically repeating the sangati. When I find my student needing some practice - to get the ideas clearly planted in his mind -- I ask him to sing the item many times over.

Of course the ideal thing to have is a bunch of students who to are quick on the uptake, who understand quickly what is being said. In the case of my daughter Anuradha for instance, I have someone who, because of many years' association perhaps, is able to grasp what I'm saying and translate the ideas in her voice not only identically but with even a special touch of her own, lent by her voice. But everyone you teach can't be like that.

I wonder whether a musician can restrict his student population only to bright people like that, and say 'No' to anyone else who wants to learn, whether he can refuse teaching assignments which come his way when teaching is done as a jeevanopayam.

For myself I follow a very strict rule. I do not accept a teaching assignment unless I know I can spare time for it and I know it won't strain me overmuch. Sometimes I'm compelled to refuse despite strong recommendation but, if I take on a worthy student, I'd like to give that tuition all I've got.

How do you teach raga, swaraprastara, niraval and such creative aspects to students ?

When Palghat Mani Iyer taught me raga, he would say, for example, Start singing Todi. I would start with a sangati. He would listen and say: OK. Now start differently. He would go on like that, getting out of me a number of starting sangati-s, a number of alternate methods of developing the raga and some sanchara-s. A sketch of the raga would emerge, with him adding on a few sangati-s of his own. Many raga phrases have come out of the great sangati-s in the various kriti-s played and sung by the masters of old -- Papa [Venkatarama] Iyer, Ariyakudi and others. These are ageless, indestructible sangati-s which can help us in getting beautiful images of the raga.

To learn the raga, therefore, one should hear a great deal of good music and one should practice a great deal. The phrases will at first be all wrong and irregular but slowly the distinct shape of the raga will emerge. One has to pass through the painful stage of apaswara-s and confusing passages. In the[Government Music] College also, I used to structure raga teaching as I have described just now, starting with an outline, using a few well-worn sangati-s that can define a raga reasonably well. But some students thought the raga was just these few sangati-s, they sang only these and called that the raga. I had to chasten them: These are only the guidelines, the framework within which the raga should be sung It is important, that, after finishing college, a student should polish up his alapana with the help of the outlines taught to him and with hard practice. Anyone who thinks he or she can come out of the college and start performing is foolish. It should never be done. The chronology is: college, followed by practice, and learning the nuances, the technical finesse, from a guru. There is much to be learnt from an experienced musician.

How about swaraprastara-s ?

In swaraprastara, there are two varieties - sarvalaghu swara-s which are simple, fluid swara korvai-s or combinations that fall in sama eduppu-s; and complicated swara-s where the eduppu or take-off is from different fractions of the tala cycle.These should be practiced until one becomes thorough. If this is done, any one of these phrases will come to the performer's help when he is doing the prastara. Within specific swara korvai-s it is possible to have variations on each. For instance, a phrase of four swara-s can be sa-sa-ri-ga, SA-ri-ga, sa-RI-ga, sa-ri-ri-ga, sa-ri-ga-ga, and so on. Any of these can be chosen depending on what the rakti of the raga demands. Experimenting with a number of these combinations and permutations is the learning of swaraprastara. These are what are called kalpana swara-s.

Of course, this is not all. One should also develop the ability to sing korvai-s of 3-7 or 3-5 or 3-9 without preplanning, on the spot. The muthaippu should seek the singer -- not the other way. A singer may have the experience of going round and round looking for the 'idam', of not being able to round off a prastara, but that would probably be his best learning experience. Once this happens he would, he should never slip up again on that score. What the singer should do to make the concert a success is another story. His swaraprastara should be done taking into account the capacity of the accompanists to support and enhance the exhibition of his artistry. While the accompanists should be able to play according to the demands of the main performer and enable the singer to give of his best, there is a countervailing responsibility as well. For example, the singer should not abandon his mridangam accompanist in search of a very intricate swara passage.

My next question is broadly in this area; it concerns voice preservation. In 1967 or thereabouts, you had some heart ailment. It seems that after this episode, your musical attainments have only been greater, not lesser. Your singing took on fresh nuances and you had no need for props of any kind. What is the secret of this ?

[Padma Narayanaswamy interrupts to say that the secret essentially is the path shown by his guru, KVN wouldn't give a recital if he had a bad throat, for instance.]

Here is where I'd like to tell you about the greatness of my guru. His 'vazhi', his method was thoroughly disciplined and oriented fully to presenting good music. For example, if he had a cold and the throat was somewhat frozen, he would not sing sanchara-s in the top sadja in the earlier part of the concert. He would select for this phase kriti-s which did not necessitate his singing at a stretch in tara stayi and he would touch the top only gently. As he kept his voice in check and released it gently, it would get adjusted and become fluid and at this point he would be able to essay comfortably the kriti Sri Subrahmanyaya namaste in Kambhoji upto the top panchama. When a musician starts ambitiously even when he has a bad throat, the voice progressively worsens till he loses his voice altogether before mangalam. But in my guru's case the voice would become better and in the latter part of the concert it would be sweet like honey.

To a large extent, you too seem to have mastered this technique. How does one achieve this ? Also, when you had the ailment, what steps did you take to conserve yourself ?

I was forgetting my music and a stage came when I thought was the end of my career. As they say, 'lrumbum thozhilurirukkak-kedum' [Rough translation: 'Too much rest is rust'] If you don't sing regularly, you can get badly out of shape.That of course doesn't mean that you should practice all the time. I have a concert engagement, let us say. I don't have to practice all the songs or the pallavi for that engagement.I simply have to tune the tambura and keep my voice at the consistent pitch and stay at that sruti. An exercise of this kind is more than sufficient to get the voice to do what one wants.

Experiences Abroad

Can you tell us about your assignments, your teaching and concert experiences abroad ?

In 1962, I joined the Government Music College in Madras as a lecturer. Musiri Subrahmania Iyer was its Principal then. In 1965, Dr. Robert Brown, the ethnomusicologist who has specialized in Carnatic music, came over from Wesleyan University in the U.S. and requested Musiri to spare my services for a couple of years so that I could teach at Middletown. This University is in Middletown, Connecticut, as you may know. Iyerval agreed to release me. So I went to Wesleyan, as did Palghat Raghu as my partner, under parallel arrangements. As artists-in-residence, our tasks were to teach Carnatic music to students there, give concerts on Fridays and go along with Dr. Brown to give concert and demonstration sessions arranged by the University. Our concerts in this period were without any violin accompaniment.

After about a year of this, we planned a coast-to-coast concert tour. Around this time, in 1966, M.S. Subbulakshmi hadcome to the U.S. to perform at the U.N.. Violinist V.V. Subrahmaniam had accompanied her. Dr. Brown wanted me to speak to Sri Sadasivam and ask him to allow VVS to stay back in America for a year and go along with Raghu and me on the concert tour. Sri Sadasivam was very happy to do this and VVS accompanied us on the tour. It was a grand experience. The tour included a memorable concert "under the stars" in the Hollywood Bowl.

What were the audiences like ? Were there many Americans ?

Americans were in the majority, yes. They were mostly students taking courses in the Humanities and some in Carnatic music. Before every concert, Dr. Brown would give an introduction, explaining our music, its lakshya and lakshana, in words which they could follow. He would demonstrate the technical aspects of the concert that was to follow--what avarnam is like, how alapana and swaraprastara are done,where a tani avartanam is played in a Carnatic music concert and what it is, etc. He would name the composers whose kriti-s I was going to sing and talk briefly about them. Really, Bob Brown has done a great deal for the dissemination of Carnatic music in the U.S.. Quite a bit of the credit must go to him. In fact, Bala, Viswa and others had also gone to Wesleyan before me and had been welcomed similarly and encouraged by Bob Brown and Jon Higgins. When Viswa went there under a scholarship, Brown and Higgins were studying in Los Angeles.

Your next visit to the U.S. was in 1974, wasn't it ?

Yes. I went to Berkeley, in California, under the auspices of an organization called the American Society for Eastern Arts.This is run by Stan Scripps and his wife Luise who was a disciple of Balasaraswati. That year there was a big group that went-Balasaraswati, myself, T.N. Krishnan, Palghat Raghu, V. Nagarajan, Nikhil Banerjee. . . even Amir Khan was scheduled to come but he died in an accident shortlybefore he was to leave. The visit was a great experience indeed. It had everything--concerts, teaching . . .

Did you go to Europe at all ?

I had participated in the Edinburgh festival in 1963. In 1977 I was one of the musicians invited to sing at the Berlin music festival. It's a well-known music fete in which both Carnatic and Hindustani music are represented. Many musicians of repute like D.K. Pattammal. K.S. Narayanaswamy and Hariprasad Chaurasia. have been invited to this festival. From Berlin we went to Holland and toured London, Paris and Geneva. The people, the foreigners who listened to our music seemed to like it.

When was your next trip to America ?

In 1983, I was invited by an organization called Bhairavi.This is run by some South Indians there: Cleveland Sundaram, Venkataraman and Anantha. They did a beautiful job organizing concerts and demonstrations for us. M.S. Anantharaman, Trichur Narendran and Padma were with me--over a period of three months. We went in September and returned in December.

And then ?

In 1984 I went to San Diego University in California under a Fulbright Scholarship. My assignment involved teaching, attending seminars, singing to students in advanced classes and answering their questions. They -- the American students -- were all people who knew music; if not our music, at least Western music. They were all intimately connected with music. Padma, who accompanied me, taught the girls.

During your two teaching assignments in America, were you teaching the students individually ? Or in groups ?

Only individual students. Occasionally there was a group of two or three, but this was rare. Invariably the students had individual schedules worked out with the teachers and they followed them diligently.

How did you find the student attitudes in the U.S. ? Is it true that some said: 'I'll give you so many dollars, teach me these songs' ?

I didn't find any such attitudes. Of course, in the various universities I taught, the schedules were all laid out, but even otherwise I don't think they [the music students] are money-minded. In fact, a young man who approached me for learning said: I'm afraid I can't pay you anything but I'm verykeen to learn. I said: It's alright. Come along. There are have-nots in America too.

Did you have problems communicating with the students ?

Right. In the beginning I wondered how I would manage it and voiced my apprehension to Brown. He assured: I haven't called you to speak; I've called you to sing. I guess I developed the skill to get my points across over two visits.This last time I even spoke in a seminar and Brown said:You are doing just fine, much better than I ever can ! Some-times, struggling to express an idea I'd ask around for the correct word. Anyhow I've been able to make myself understood. So that's that.

Concert Accompaniments

Do you have any views on the role of accompanists in a concert ?

A violin accompanist has an unenviable role to play. He should invariably be more knowledgeable than the singer. Because he has to play for so many main performers, he necessarily has to know more kriti-s and be better at technique and be familiar with a variety of styles. But all the same he has to underplay and subjugate his artistry to that of the singer. A soloist can play at will and exhibit everything he has but not an accompanist. The violinist has to understand the quality and quantity of sound to be given for a particular singer, for a particular song, even for a particular prayoga in a kriti. The song being sung should be heard by him clearly, this is of paramount importance. Kumbakonam Rajamanickam Pillai used to hold the sound of his violin at a level where he could hear the singer well. Similarly, Palghat Mani Iyer's playing depended entirely upon the voice of the singer. The softer the voice, the softer his mridangam sound would be. For a singer with ghana saareeram he would play with more force.

How much of their own virtuosity can the accompanists exhibit ? Isn't there a problem for them either way, in that if they show their virtuosity they are accused of overshadowing the singer and if they underplay, the listeners accuse them of lackluster or dreary performance.

There was a violinist named Tiruvalangadu Sundaresa Iyer,also called Suswara Sundaresa Iyer. Do you know how he used to play ? If the main singer took five minutes [to delineate a raga], he would take only one-and-a-half or two. But in that time he would show everything the main artist did and more. The raga would be rasa-purvaka and ranjaka to the core [full of rasa and a pleasure to listen to]. He would be only sketching the raga, mind you, but it would have the impact of a complete alapana. Some accompanying violinist might say, for instance: The singer sang for five minutes, but I played only for 4 3/4 minutes. What was the need to play for 4 3/4 minutes, pray ? In any case, duration by itself is not the main issue. If the circumstances warrant it, there'd be no harm even if he played for longer. What is important is the presence of mind of the accompanying violinist, his quick grasp of the situation and the aptness of his response. Proportion is everything in a concert. This was what endeared M. Chandrasekharan to me when he accompanied me recently in a Gayana Samaja concert in Bangalore. I was singing Saveri as a prelude to a pallavi and did it in three parts-first upto the panchama, then the upper reaches and then the descent. At each stage when I gave him the floor, he played briefly and only upto the point which I had sung. This kind of understanding heightens the listening pleasure and the singer's own mood considerably.

Would you therefore expect your violin accompanist merely to follow your sangati-s faithfully, or would you allow something more creative, something which spurs you to reach greater heights ?

Certainly the latter, certainly some creative accompaniment -- but the accompanist should be capable of that, shouldn't he ? If he is not, it would be much better off if he were to conclude his tani-s quickly and underplay totally. He should at least be intelligent enough to realize his limitations and not play out the 'full length of time' as preconceived by him. In fact, he would be spoiling the concert and annoying the listeners as well if he did that; if he were to show no virtuosity at all, the singer can try and make up for that lack with his talent. A kutcheri needs a lot of teamwork, really.

Do you specify accompaniments you would like to have for your concerts ? Do you think a musician can or should do this ?

A singer should be ready to sing, regardless of who is accompanying him. He might have ideas of his own, that such and such a violinist or mridangam player would suit him best. But he must not enforce it on the organizer. Of course people, listeners who have heard his concerts for a long time, might feel that he comes off best in a particular combination and they sometimes express a wish that he should sing with those sidemen. In such cases, if a sabha secretary were to ask me for my suggestions regarding the sidemen, I'd say: Do as you please, but you might consider so-and-so. I sometimes recommend a violinist who hasn't played at all with me, so that I can get a new experience and the listeners also have a variation.

When you sing with a new accompanist, do you make any special effort to ensure that you blend well ?

Nothing of that kind. I don't think it's required in our music to make advance preparations. The artists often meet only on the dais-so arranging the concert items in advance or rehearsing is out. We have to learn the grammar and the sahitya-s and the pathantara-s well before we get on the concert platform; so it isn't necessary to know each other. A musician who has reached a certain level should be able to sing to any accompaniment; the same goes for the sidemen in reverse.

But do accompanists come to you sometimes to prepare for a concert ?

Yes, they do sometimes. But more often than not, a violinist who has played for a few singers learns the different styles and acquires the skill to interpret the style of a new singer within the first couple of items in a concert.

Ragam-Tanam-Pallavi

As you know, the Sruti Foundation has been implementing a project to restore ragam-tanam-pallavi to its proper place and to promote special pallavi concerts. You were, in fact, the first musician to be featured in the Project's pallavi series in Madras. Can you share your views on the significance of ragam-tanam-pallavi in Carnatic music ?

Ragam-tanam-pallavi is indeed an important item in our music, in our kutcheries. As a rule, it comprises an elaborate ragam, tanam and a pallavi in 4-kalai chaukkam. If a musician wants to give the pallavi the pride of place in his or her concert, this multi-tempo rendering is a must. There are many beautiful pallavi-s of this genre. If you examine some old-time pallavi-s, you'll note the words are very few, but the pallavi will be sung in 4-kalai, so that there is more scope for intricate niraval. Then there are nadai-pallavi-s too.In a concert, there are times when the pallavi is the main item. At other times, a major kriti in a major raga may itself come off so well in fulsome detail, that a pallavi may seem superfluous. In such an event, a short pallavi will be inorder--not a 4-kalai affair, something smaller--but it should have substance, like a difficult tala or a tricky eduppu. Pallavi-s should be sung more and more but we can't expect to hear a pallavi in every concert. The short duration of kutcheries these days makes it difficult. If we try to give representation to many composers, as we are expected to do, then we have very little time left for a detailed pallavi. We are also expected to include as many musical forms in a kutcheri aswe can-varnam, javali, padam, tillana, ashtapadi, bhajan, tarangam, viruttam and so on. In the old days there were no such constraints and one could sing just four or five items, including a pallavi in a recital.That's why I think SRUTI's Pallavi Project is an excellent idea. When you explore a pallavi properly, you need two hours and more--which you can get in a special program like that. Such special pallavi-oriented concerts should beheld widely, but in regular concerts a pallavi should not be insisted upon even as it should not be avoided totally. It should just happen. It shouldn't be forced. The motto for a general concert must be: sing anything but don't allow the rasa to be affected adversely. However, for the prime-time concerts in a place like the Music Academy, it's important to include an elaborate Pallavi.